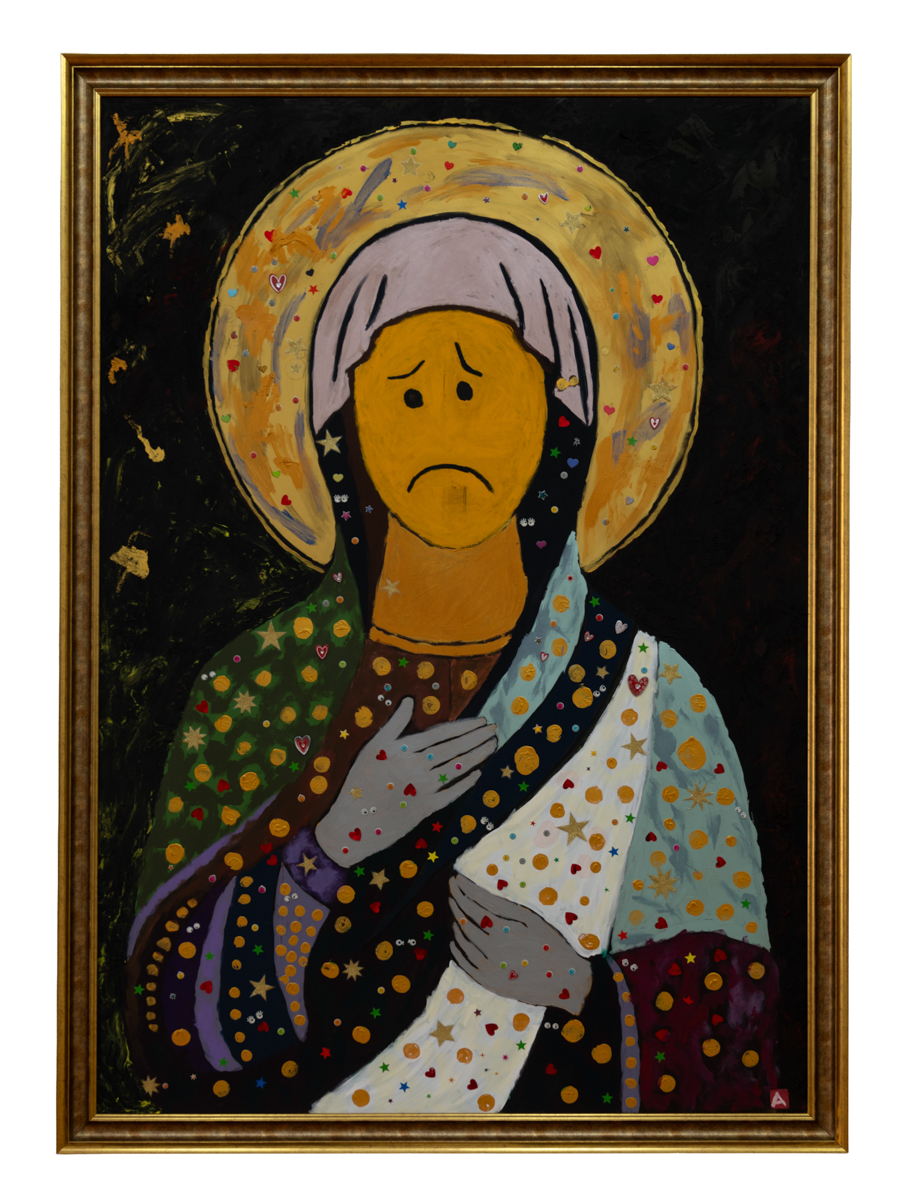

Madonna dell"Emoji, protettrice dei Polpi (Sfânta Emojiului, ocrotitoarea caracatițelor)

An2025

Tehnicăacrylic on canvas, mixed media

Dimensiuni200 x 140 cm

12 000 EUR - link de platǎ disponibil la finalul prezentǎrii (payment link available at the end of presentation)

RO/EN

În tradiția iconografică italiană, fiecare Madonnă avea un patronat — proteja marinarii, bolnavii, copiii, pe cei pierduți în drumul spre casă. Madonna din această lucrare protejează caracatițele, ceea ce pare absurd doar până înțelegi de ce: caracatița are trei inimi, sânge albastru și opt brațe care gândesc independent de creierul central, adică e probabil cea mai generoasă formă de inteligență apărută vreodată pe planeta asta, un organism care nu poate să nu atingă lumea din jur, care simte distributiv, cu tot corpul, fără să-și filtreze senzațiile printr-un singur centru de comandă. Madonna le protejează pe ele pentru că noi am încetat demult să mai avem nevoie de protecție divină — am ales-o pe cea algoritmică.

Chipul Madonei e un emoji trist. Nu e o glumă și nu e ironie, e cel mai precis lucru pe care l-am putut picta, pentru că exact asta am făcut cu expresia umană a suferinței: am redus-o la un cerc galben cu gura în jos, la un simbol pe care îl trimiți între două mesaje despre ce ai mâncat la prânz. Emoji-ul trist e poate cea mai sinceră și în același timp cea mai degradantă formă de empatie contemporană — spune „sufăr" într-un limbaj în care nu poți suferi cu adevărat, pentru că limbajul însuși a fost construit ca să nu dea voie durerii să deranjeze pe nimeni mai mult de o secundă.

Veșmintele Madonei păstrează structura mantiei bizantine, dar pietrele prețioase care în icoanele tradiționale simbolizau devoțiunea și sacrificiul material al credinciosului au fost înlocuite cu inimioare, steluțe, emoji-uri — confetti-ul digital al validării sociale, aceleași simboluri pe care le aruncăm zilnic spre orice ne face să simțim ceva timp de trei secunde înainte să dăm scroll mai departe. Diferența dintre o piatră prețioasă donată unei biserici în secolul al XII-lea și un emoji cu inimioară trimis pe Instagram în 2026 e exact distanța pe care am parcurs-o ca specie între devoțiune și distragere, iar tabloul meu nu face altceva decât să le pună una lângă alta și să te lase să decizi singur dacă drumul a fost în sus sau în jos.

Compoziția e deliberat clasică — bust frontal, mâini la piept, aureolă, fond întunecat — pentru că nu am vrut să parodiez icoana, ci să pictez una nouă, una adevărată, care să arate exact ce venerăm noi acum. Dacă un călugăr din Constantinopol ar fi trăit în 2026 și ar fi fost cinstit până la capăt, asta ar fi pictat: o Madonnă cu față de emoji și mantie cu stickere, care nu mai salvează suflete pentru că sufletele au fost înlocuite cu avataruri, și care protejează caracatițele pentru că ele sunt ultimele creaturi care mai știu să simtă fără să posteze un story despre asta.

------------------------------

In Italian iconographic tradition, every Madonna had a patronage — she protected sailors, the sick, children, those lost on their way home. The Madonna in this work protects octopuses, which sounds absurd only until you understand why: the octopus has three hearts, blue blood, and eight arms that think independently from the central brain — meaning it is probably the most generous form of intelligence ever to appear on this planet, an organism that cannot not touch the world around it, that senses distributively, with its entire body, without filtering sensations through a single command center. The Madonna protects them because we stopped needing divine protection long ago — we chose algorithmic protection instead.

The Madonna’s face is a sad emoji. It’s not a joke and not irony; it is the most accurate thing I could paint, because this is exactly what we have done to the human expression of suffering: we reduced it to a yellow circle with a downward mouth, to a symbol you send between two messages about what you ate for lunch. The sad emoji is perhaps the most honest and at the same time the most degrading form of contemporary empathy — it says “I suffer” in a language in which you cannot truly suffer, because that language was built to prevent pain from disturbing anyone for more than a second.

The Madonna’s garments preserve the structure of the Byzantine mantle, but the precious stones that in traditional icons symbolized devotion and the material sacrifice of the believer have been replaced with hearts, stars, emojis — the digital confetti of social validation, the same symbols we fling every day at anything that makes us feel something for three seconds before we scroll on.

The difference between a precious stone donated to a church in the 12th century and a heart-emoji sent on Instagram in 2026 is exactly the distance our species has travelled between devotion and distraction, and my painting does nothing more than place them side by side and let you decide whether that path went upward or downward.

The composition is deliberately classical — frontal bust, hands at the chest, halo, dark background — because I didn’t want to parody the icon but to paint a new one, a real one, one that shows exactly what we venerate now.

If a monk from Constantinople had lived in 2026 and had been honest to the end, this is what he would have painted: a Madonna with an emoji face and a mantle covered in stickers, who no longer saves souls because souls have been replaced by avatars, and who protects octopuses because they are the last creatures that still know how to feel without posting a story about it.

RO/EN

În tradiția iconografică italiană, fiecare Madonnă avea un patronat — proteja marinarii, bolnavii, copiii, pe cei pierduți în drumul spre casă. Madonna din această lucrare protejează caracatițele, ceea ce pare absurd doar până înțelegi de ce: caracatița are trei inimi, sânge albastru și opt brațe care gândesc independent de creierul central, adică e probabil cea mai generoasă formă de inteligență apărută vreodată pe planeta asta, un organism care nu poate să nu atingă lumea din jur, care simte distributiv, cu tot corpul, fără să-și filtreze senzațiile printr-un singur centru de comandă. Madonna le protejează pe ele pentru că noi am încetat demult să mai avem nevoie de protecție divină — am ales-o pe cea algoritmică.

Chipul Madonei e un emoji trist. Nu e o glumă și nu e ironie, e cel mai precis lucru pe care l-am putut picta, pentru că exact asta am făcut cu expresia umană a suferinței: am redus-o la un cerc galben cu gura în jos, la un simbol pe care îl trimiți între două mesaje despre ce ai mâncat la prânz. Emoji-ul trist e poate cea mai sinceră și în același timp cea mai degradantă formă de empatie contemporană — spune „sufăr" într-un limbaj în care nu poți suferi cu adevărat, pentru că limbajul însuși a fost construit ca să nu dea voie durerii să deranjeze pe nimeni mai mult de o secundă.

Veșmintele Madonei păstrează structura mantiei bizantine, dar pietrele prețioase care în icoanele tradiționale simbolizau devoțiunea și sacrificiul material al credinciosului au fost înlocuite cu inimioare, steluțe, emoji-uri — confetti-ul digital al validării sociale, aceleași simboluri pe care le aruncăm zilnic spre orice ne face să simțim ceva timp de trei secunde înainte să dăm scroll mai departe. Diferența dintre o piatră prețioasă donată unei biserici în secolul al XII-lea și un emoji cu inimioară trimis pe Instagram în 2026 e exact distanța pe care am parcurs-o ca specie între devoțiune și distragere, iar tabloul meu nu face altceva decât să le pună una lângă alta și să te lase să decizi singur dacă drumul a fost în sus sau în jos.

Compoziția e deliberat clasică — bust frontal, mâini la piept, aureolă, fond întunecat — pentru că nu am vrut să parodiez icoana, ci să pictez una nouă, una adevărată, care să arate exact ce venerăm noi acum. Dacă un călugăr din Constantinopol ar fi trăit în 2026 și ar fi fost cinstit până la capăt, asta ar fi pictat: o Madonnă cu față de emoji și mantie cu stickere, care nu mai salvează suflete pentru că sufletele au fost înlocuite cu avataruri, și care protejează caracatițele pentru că ele sunt ultimele creaturi care mai știu să simtă fără să posteze un story despre asta.

------------------------------

In Italian iconographic tradition, every Madonna had a patronage — she protected sailors, the sick, children, those lost on their way home. The Madonna in this work protects octopuses, which sounds absurd only until you understand why: the octopus has three hearts, blue blood, and eight arms that think independently from the central brain — meaning it is probably the most generous form of intelligence ever to appear on this planet, an organism that cannot not touch the world around it, that senses distributively, with its entire body, without filtering sensations through a single command center. The Madonna protects them because we stopped needing divine protection long ago — we chose algorithmic protection instead.

The Madonna’s face is a sad emoji. It’s not a joke and not irony; it is the most accurate thing I could paint, because this is exactly what we have done to the human expression of suffering: we reduced it to a yellow circle with a downward mouth, to a symbol you send between two messages about what you ate for lunch. The sad emoji is perhaps the most honest and at the same time the most degrading form of contemporary empathy — it says “I suffer” in a language in which you cannot truly suffer, because that language was built to prevent pain from disturbing anyone for more than a second.

The Madonna’s garments preserve the structure of the Byzantine mantle, but the precious stones that in traditional icons symbolized devotion and the material sacrifice of the believer have been replaced with hearts, stars, emojis — the digital confetti of social validation, the same symbols we fling every day at anything that makes us feel something for three seconds before we scroll on.

The difference between a precious stone donated to a church in the 12th century and a heart-emoji sent on Instagram in 2026 is exactly the distance our species has travelled between devotion and distraction, and my painting does nothing more than place them side by side and let you decide whether that path went upward or downward.

The composition is deliberately classical — frontal bust, hands at the chest, halo, dark background — because I didn’t want to parody the icon but to paint a new one, a real one, one that shows exactly what we venerate now.

If a monk from Constantinople had lived in 2026 and had been honest to the end, this is what he would have painted: a Madonna with an emoji face and a mantle covered in stickers, who no longer saves souls because souls have been replaced by avatars, and who protects octopuses because they are the last creatures that still know how to feel without posting a story about it.

Vândut